think systems, not humans

Think about systems, not about humans.

Yesterday, I met a new friend for tea in San Francisco. Over a couple of hours, we shared our stories and explored how we each think. We had originally crossed paths at a very Bay Area networking event—imagine a pool party with a panel discussion about AI. During the event, we touched on her work in systems thinking and regenerative models, which piqued my curiosity. What exactly did she mean by systems thinking?

The term "systems thinking" has different meanings in different contexts. The main one I'm familiar with is in the engineering or design side of tech, where one considers and plans out the overall patterns and fractals of a startup's code or design. A design system will have its set of protocols, including a color palette, typography, and user flow guidelines. For example, designers might decide whether to use modals for displaying important information or stick to inline notifications. They might also consider how to structure navigation menus—whether to use a traditional drop-down menu or an innovative sidebar—based on the overall user experience. Additionally, they may establish rules for consistent button placement across the platform, ensuring a seamless and intuitive interface. All these decisions are interconnected, contributing to a cohesive and functional design system.

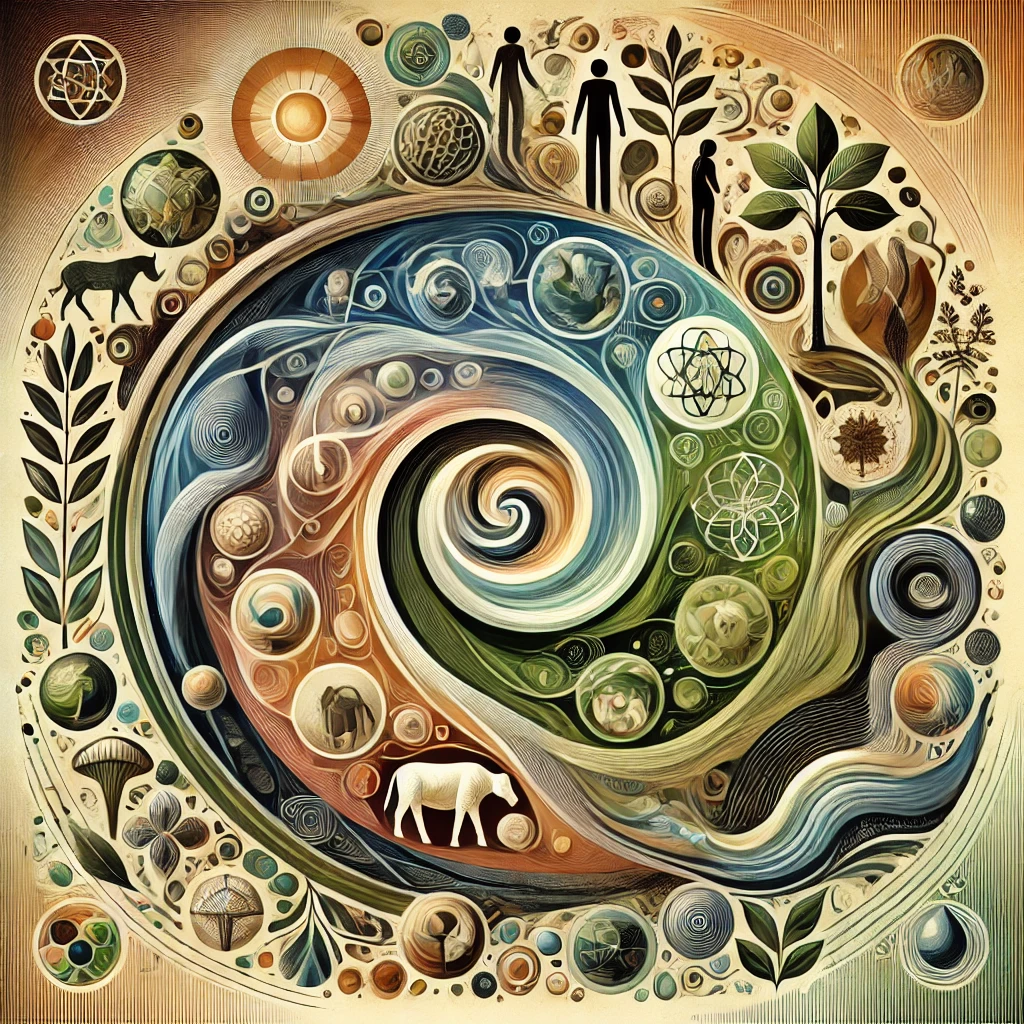

However, she was talking about a broader form of systems thinking, one that applies to how we live, how we think, and how we implement change. This type of systems thinking is best understood in contrast to human-centered design. Rather than making humans the focal point and primary beneficiaries of products and services, broader systems like communities, flora, fauna, and the environment are the primary considerations. How do what we do and what we build affect the ecosystem in which we live?

A fundamental premise of this framework is that humans are one with the systems around them. We are all part of a larger whole—composed of other people, yes, but also of the land, animals, and the Earth around us. My friend pointed to her marvel and awe of the seasons and nature as examples of natural systems worthy of emulation. When our scope of service expands to include the systems and ecosystems in which we live, regenerative models take precedence. How can what we build create self-sustaining systems that allow all to flourish?

Another idea she shared about venture funding struck me. Rather than investing in individual founders, betting that they alone will change a broader market with their groundbreaking unicorn idea, investors should instead look to self-organize and fund groups of founders who can collectively make broader, systemic changes. She didn’t have a name for this, but I'll suggest a few: a federated investing strategy or a federated collective of investors. I like the idea of a governed body of individuals collectively agreeing on a set of values and using their financial power to influence or change a broader industry. This general principle isn't new—we find it throughout history that collectives, unions, coalitions, and other organized bodies of individuals often provide the mass, force, and energy sufficient to make larger change. It's not the lone wolf but the pack that hunts most effectively.

How can you apply systems thinking to broaden your impact?